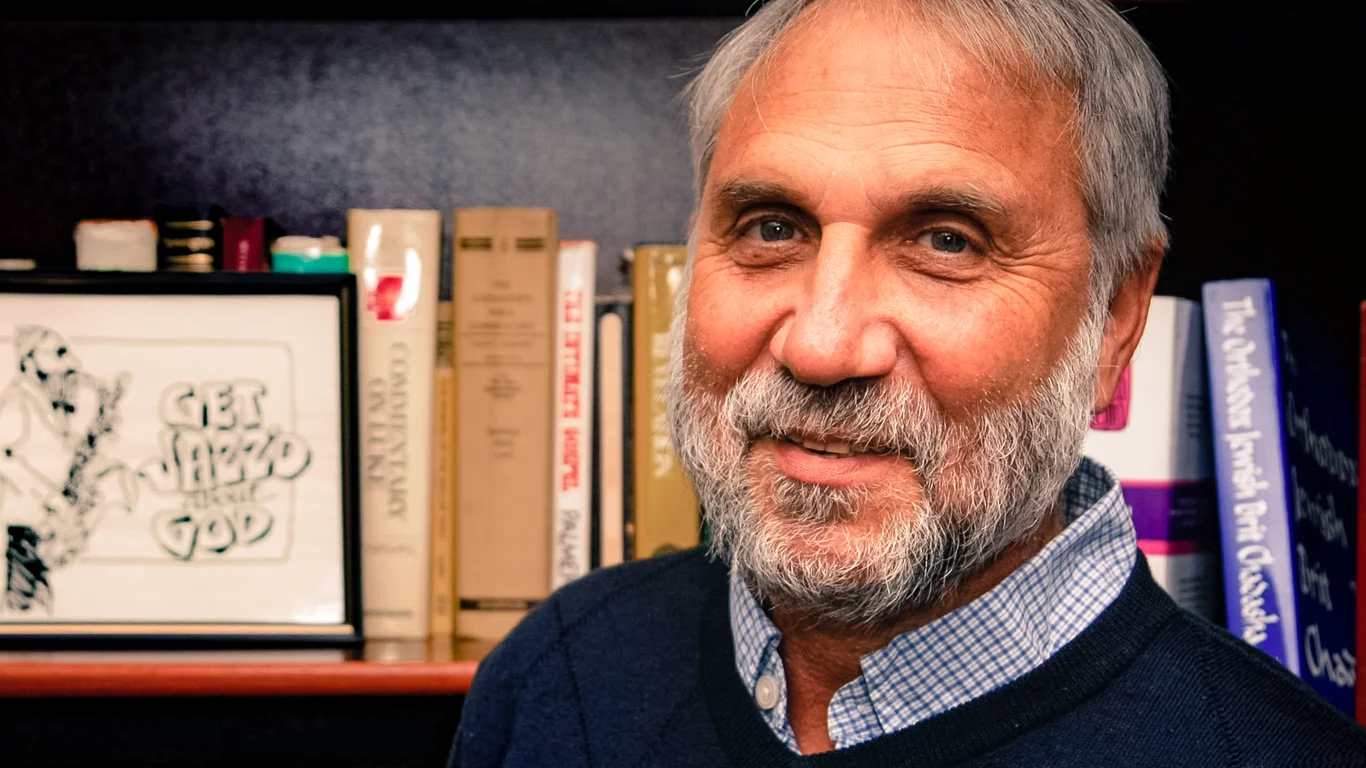

Jhan Moskowitz

Some survivors do not tell their kids anything. They just don’t. Some survivors tell their kids everything. When I was a little boy, I crawled into my father’s lap and asked, “What is that number on your arm?” He didn’t flinch, he told me he was in the concentration camps. He grew up outside of Lodz, Poland, and spent four and a half years in several work camps as well as Auschwitz. He did not explain in detail what he had been through, but he told me more as I got older. I asked him if he went to school, and he said that Jewish kids didn’t get to go to high school. He told me that when he was growing up in Poland the week of Passover was terrible; his family never left the house. If they did, the priest would come out of the church with a big cross and kids would throw rocks and call them “Christ-killers.”

My mother’s name is Lilly, and she grew up in Maramush, which is between Hungary and Romania. She was in the camps for almost two years. Because my parents were Holocaust survivors, I grew up with a keen understanding of the fact that I was Jewish. There was never a time in my life when I did not recognize the great price our people paid for our existence.

When I got sick as a child I remember feeling a moral obligation to get better. Both my mother and father made me feel guilty if I got sick. I had to be strong and live to defeat the Nazis’ intentions. Knowing the pain and suffering my parents endured meant that I could not complain about incidental problems. When I came home one day and said, “There is nothing to eat, let’s go out,” my father said to me sternly, “There is bread, there is a meal!” How can you tell a man who was so malnourished that eating a full meal would have killed him when he was liberated, that there is not enough food?

I constantly lived with a sense that the Holocaust could happen again. I’d visit someone’s apartment or house and immediately I’d look under the stairs and think that would be a good place to hide. Most kids don’t think like that. There was also an “us and them” mentality. My father was a very joyous, loving man. But he had a terrible hatred of Germans. He worked through this later in his life, but when I was younger he’d say, “Don’t turn your back on a German, they’ll stab you in the back.” I was raised in a pluralistic American society, and this was contrary to the values taught at school and in my somewhat liberal home. Clashes were inevitable.

I remember once I came home and told my family I was dating a German girl. Now, she wasn’t German; she was American. Maybe one of her distant relatives a hundred years ago was German. But she wasn’t Jewish, and it was like I had brought an SS guard into the house. My father’s family was one of the most important things in his life, and so he wanted to protect us as much as he could.

My father really celebrated the fact that he was alive. When I asked him his birthday, he told me his age from the date he was liberated from the camp. He said he felt like he was brought back from the dead, or re-born. I learned to appreciate life from him.

But there was a bad side to being a child of a survivor. Despite his loving nature, my father had a horrendous temper. I remember the intense fury my father would unleash. Only later did I begin to understand that his flood of rage was a result of constantly having to suppress his emotions while he was in the camps.

I felt sad for my father. I felt he was ripped off, that his youth was stolen, that his faith was stolen. I found it remarkable that he was able to survive and to love and to laugh again. It’s a great testimony to the strength of the human spirit, but I still feel like the Nazis robbed him.

In 1967 I went to Israel to work on a kibbutz. One day, someone on the kibbutz found me and said, “There’s a police officer to see you.” Of course, I was apprehensive. The police officer walked over to me, and started crying and hugging and kissing me. In broken Hebrew, he told me his name was Kozak. When the Nazis invaded Poland, they hung Kozak’s sister, my father’s first wife. My father had never told me he was married before. He never told me the Nazis hung his first wife.

I decided to visit Kozak in his home in Haifa. I was standing on the street with him and his family, when suddenly an old Jewish man came running down the street, and he said, “Is this Moishe’s son?” Kozak smiled and said yes. And the man just fell upon me and he kissed me and he started telling me how much my father meant to him. I learned that because my father was a tailor, he had access to certain things like potatoes from the camp chef. He made sure people were fed. This man said my father saved his life, and the lives of many others.

That was a very telling moment, to discover for certain that my father was a hero. When I asked my father why he never told me these stories, he said he didn’t feel as though he was keeping it from me, it just never came up.

The Holocaust has shaped much of my thinking and my worldview. I think the idea of humanism died fifty years ago; humanity can no longer believe that we are evolving into a better people. Germany was the pinnacle of humanism, and yet it brought us to Treblinka. If ever there was a doubt regarding the sinful human nature, it was resolved by the Nazis. We can have no more illusions of progress. Humanity is so steeped in its own sin that it was unable to resist even the most blatant of evil.

The person who has suffered through this kind of evil wants to understand how God can allow such suffering. There is a point at which you come to believe that you are allowed to go through the consequences of life, whatever they may be, because there is a greater good that is going to happen. I say that with great reservation. I can’t apologize for God; I can’t give the correct theological answer to the question of pain, not to the one who has gone through it. It’s not that God was powerless. It wasn’t that God wasn’t able and it wasn’t that he didn’t care. It’s just that somehow, in God’s mysterious ways, something good will come of this. I guess I just wait.

When I became a believer in Jesus, I came to my father with a Yiddish New Testament. I opened it up to Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. I wanted my father to meet the real Jesus, not the one that’s portrayed as a tank rolling into his neighborhood or the one who turned the gas on his parents, but the Jesus that talks about love.

The most perfect demonstration of God’s love throughout all of history is the offering of the Messiah. So my father read the story, and for the most part he accepted that Jesus was a Jew and that there was good reason for me to be drawn to him. Then he got to the place where it says, “…forgive us as we forgive those who trespass against us.” He closed the book and said, “I can’t do this, I can’t.” He looked at me and said, “I would rather go to hell, knowing I could take the Nazis with me, than forgive them.” I said, “Dad, they still win that way.” He said, “I can’t.”

I once was asked by someone to extend forgiveness to the Nazis for what they did. You can’t imagine what that did to me. So much of my identity was wrapped up in the consequences I had suffered because my parents were survivors. I sat down and prayed and said, “God, you really have to help me.” I came to a place that my father couldn’t come to. Forgiveness is not absolution, forgiveness is letting go of the hate. I don’t think my father was ever able to do that. The Holocaust did that. For many of us, it ripped off the ability to forgive. And that’s the worst thing.

(Jhan died suddenly after slipping on a wet stairwell in a subway in 2012 in New York City)